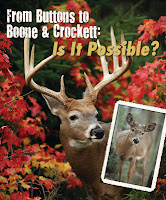

As a teen, I believed age and quality food sources were the magical ingredients needed to produce a buck with the minimum 170 inches required for entry into the Boone and Crockett record book. As time passed, my thinking changed. In reality, there is no guarantee a buck will actually produce a Boone and Crockett rack. The process of getting a whitetail from the button buck stage to the B&C category is a mystical journey that includes a complex assortment of variables. It takes four basic ingredients to produce a buck with a 170-inch rack: genetics, habitat, herd management and age.

Essentially, the environment required to produce high numbers of

B&C bucks does not exist, at least in the wild. Further, even if an area

provides the four ingredients, those components must align flawlessly to

produce several record class whitetails. Even perfect conditions do not guarantee

B&C bucks. To see how tough it is to raise a whitetail from a fawn to a

Booner, let’s look at two scenarios — the real world and a controlled environment

— to see how various factors affect antler growth. The real world refers to any

place in North America with free-roaming whitetails. These deer must cope with

everything nature and humans throw at them. The stress heaped on them often

reaches absurd levels, resulting in suppressed antler growth. I believe stress

on free-ranging deer is cumulative, and antler growth is suppressed in varying

degrees depending on how many stress factors are placed on a herd.

ENVIRONMENT

Whitetails still deal with environmental stress factors even when

human activity is removed from an area. For example, in remote southern locations,

extreme heat and parasites heavily burden deer herds. In northern climates,

whitetails have a different problem: brutal winters with deep snow and

bitter-cold temperatures. Winter’s stress can severely suppress antler growth,

especially when it leads to substantial over-browsing of habitat. No matter

where it occurs, drought is a major suppressant of antler growth, especially if

it occurs during the critical antler-growing season of April through July.

Bucks need large quantities of lush nutritional food to realize their antler-growing

potential. Insects are another environmental stressor. Swarms of insects have

been known to kill domestic animals, but they also kill deer.

FOOD

Most deer need around a ton-and-a-half of food per year to

maintain optimum health. For the best antler growth, it’s critical that the

nutritional composition of food is high at all times. Therefore, during the

antler-growing season, food sources must be high in protein and provide essential

vitamins and minerals. During the non-antler-growing season — fall through

early spring — food sources need to be high in carbohydrates to provide deer

with the high energy levels they need. The ability of the habitat to support

the wildlife living in it is a key to antler growth. Bucks can grow impressive

antlers when they receive a variety of highly nutritious foods. However, these

food sources can disappear quickly when too many deer are on a property. Therefore,

bucks living on overpopulated range will not always grow large racks, at least not

what they are capable of. This is why it is so important to keep the whitetail

population in line with the range’s carrying capacity. Soil quality can be a

limiting factor on the benefit of farm crops and food plots in the quest to

produce the biggest bucks. It is no coincidence that some of the biggest bucks come

from regions with fertile soil. For example, the Midwest’s “Grain Belt”

contains some of the most productive soil in North America. It's easy to

understand why the region has produced more than 60 percent of the whitetail

bucks entered in the B&C record book.

|

| High protein food plots like this Imperial Whitetail Clover food plot can help reduce nutritional stress on all deer. |

POPULATION

A region’s deer population is as important as food availability in

allowing a buck to reach maximum antler potential. Antler growth suffers when

an area becomes too densely populated. For the past 20 years, I have raised

whitetails for behavioral studies. Early on, it became obvious that whitetails

are very sensitive to overpopulation, and a buck’s antler growth suffers if

there are too many deer in its environment. Many studies of wild free-ranging

deer have also confirmed what I have observed in high-fenced deer operations.

ADULT DOE-TO-ANTLERED-BUCK RATIO

A deer herd’s sex ratio is a significant suppressant of antler

growth, and it does not take many deer to skew the odds against bucks. For

example, antler growth suffers in areas that have more than three adult does

for every antlered buck. When herds exceed that ratio, the rut stretches to a danger

point for bucks — especially mature bucks. A 2-to-1 ratio is not bad, but for

maximum growth potential, a 1-to-1 ratio is ideal. The rut lasts about 45 days

in areas with balanced ratios. When a doe comes into estrous, she takes a buck

on a two- to-three-day ride he cannot control. Because a buck does not know

when enough is enough, he gets himself into all kinds of trouble — often

trouble he can’t recover from. Therefore, when the adult doe-to-antlered buck

ratio exceeds three adult does for every antlered buck, the rut can last 90

days or more. This is dangerous, because in the North, it means the rut will

stretch into winter. In turn, rutting bucks enter this critical period so worn

down they cannot recover before their antlers begin to grow in April. In such

instances, it is not uncommon for mature bucks to die from additional winter

stress.

|

| A deer herd's sex ratio can be a significant suppressent of antler growth, and it doesn't take many deer to skew the odds against bucks. |

THE RUT

If all those stresses aren’t enough, bucks receive another dose of

pressure when the rut begins. If you add the fierce competition waged between

bucks to the list of stress factors they endure the rest of the year, it is

easy to see why free-ranging bucks have difficulty reaching their full antler

potential. In good range, bucks are rolling in fat when the seeking phase of

the rut begins. However, during the two-week period just before full-blown

breeding, bucks begin to move constantly, searching for estrous does. This

nonstop dash to ensure survival of the species involves everything from chasing

to scrape-making to rubbing to fighting. Clearly, bucks expend a lot of energy

during the rut, and they often do so without eating. This increases strain on

their bodies.

PREDATION

Predation is another stress factor that affects antler growth

potential. Dogs, coyotes, wolves and humans kill hundreds of thousands of deer each

year. However, non-contact predation also affects deer. Non-contact predation

includes the mere presence of predators. Several projects conducted by Aaron

Moen of Cornell University have indicated this form of stress can make bucks

grow underdeveloped antlers. The bottom line is any form of predation places

some stress on whitetails, which can have a negative effect from a physical

standpoint and prevent them from reaching their full growth potential.

CONTROLLED LESSONS LEARNED

By reducing the stress associated with the factors listed above,

you can improve the odds of watching a buck fawn grow into a B&C-class whitetail.

Some people might argue that it is impossible to reduce some of the stress

factors because of the region in which they live. However, today’s high-tech

age has made it possible to create controlled environments in which the sources

of stress can be manipulated. Many deer breeders have experimented and

discovered what it takes to raise trophy class antlered bucks. Of course, their

work is done behind high fences, where deer are raised in relatively

stress-free conditions. To produce big-racked bucks, the better deer breeders

have become students of genetics, and they meticulously study individual deer

for desired characteristics. They also look at numerous other factors they need

to build upon for full antler potential. One of the most critical is habitat

because if the buck’s environment is not right, it doesn’t matter what kind of

genetics he has because he will not reach his full potential. This means trying

to control and improve everything from diet, to natural settings, to the number

of deer a buck interacts with. What deer breeders have learned is that every

whitetail buck needs to go into a new antler-growing season in great health. Therefore,

if a buck’s bone marrow and body condition are not in top condition when the

sun says, “Start growing antlers,” they can’t reach their full antler

potential.

REALISTIC EXPECTATIONS

When analyzing the antler potential of various regions of the

country, I look at how an area stacks up against the six stress factors

mentioned. If all six affect an area, there is strong reason to believe top-end

potential will not exist. However, if only two factors affect a region, I want

to hunt there because I know it probably holds many big bucks. That is not to

say I’m a trophy hunter. In fact, I believe many hunters put too much emphasis on

the magic antler score of 170. It is unrealistic for hunters to believe they actually

stand a chance of killing a buck that big in the wild, where there are no high

fences. I have hunted wild, free-ranging whitetails more than 40 years, and

only twice have I killed a buck that grossed more than 170 inches on the

B&C scale. In other words, a 170-class wild, free-ranging buck is a freak

of nature. When hunters ask me what kind of bucks they can expect to see in places

like western Canada, Iowa and Texas, I tell them not to base their goals on

what they read in magazines or see on television. Be realistic and try to find

out what the average size is for bucks in a given area. I believe a realistic

expectation for hunts in the best deer habitat in North America is 140 to 150

B&C. The bottom line is this: Considering all the stress factors that weigh

on a deer herd, it is difficult to find 150- inch bucks in the wild. In many

places, few — if any — exist. In fact, research tells us that the 140- and

150-inch bucks living in Saskatchewan, Wisconsin and New York could easily be

160- to 170- inch bucks if they lived in controlled environments. Further, most

deer researchers will tell you that heavy stress — whether drought, predators, severe

winters or other environmental factors — can suppress antler growth by 20

percent or more.

CONCLUSION

There is a lot more to getting a whitetail buck from buttons to

B&C antlers than meets the eye. In fact, for most bucks roaming North America,

it is almost impossible. Future hunters will probably kill huge bucks that

rival the whitetails taken by Milo Hanson and James Jordan. These awesome bucks

are a part of the mystery of life, just like seven-foot-tall basketball players

and home-run hitters such as Hank Aaron and Babe Ruth. However, is it realistic

to think the road from buttons to B&C is a given? No way. For my money, 140

to 150 inches is about as good as it gets in the best fair-chase environments. One

thing is certain: Stress hurts the hat size of every buck in the wild.

A Real World Example

The four photos that accompany this sidebar show

what can happen when good food, average genetics and age come together. This

buck was born in the wild on our farm in spring 1995. During summer 1995, our

35-acre research enclosure was built. Despite going to great pains to make sure

no wild deer were trapped inside, this buck — which was a fawn at the time —

managed to elude us when we drove out the wild deer. After gaining permission

to keep the buck, time took over. With the enclosure’s great food sources and low

deer population, the buck thrived. As a yearling, it had a beautiful 7- point

rack.

|

| 1.5 years old |

At age two, the buck sported a rack that scored 122 Boone and Crockett.

By the time the buck was three, it carried antlers scoring a touch more than

150 B&C. Then at age four, the buck, which we named “Spook,” had a rack

that scored 164 Boone and Crockett. Unfortunately, in December of his fourth

year, this buck was involved in a fight with another mature buck in the

enclosure and died after breaking his neck. It is anyone’s guess what his

antlers would have looked like from age five to seven, when bucks generally grow

their biggest racks. However, this buck, born in the wild on our farm, is a

testimony to what can be expected when age and nutrition are blended together

and is further proof of what quality deer management can bring to the table.

|

| 2.5 years old |

|

| 3.5 years old |

|

| 4.5 years old |

END NOTE Because

this buck is a real-world example of what can happen when age is allowed to

play itself out, these images offer guidance for QDM harvest practices. As mentioned,

one of the first steps in a quality, deer management program is to place

yearling bucks off limits. However, what is seldom mentioned is the importance

of also letting the 2- 1/2 -year-old bucks walk. In most cases, there is a

significant jump in antler growth at every age from 1-1/2 to 4-1/2. However,

the increase in antler size between 2- 1/2 and 3-1/2 years and then 3-1/2 and

4-1/2 is most impressive. As you can see, this buck grew from a 120- to a

150-class buck between 2-1/2 and 3-1/2 years. Therefore,

most QDM participants strive to ensure that no buck is harvested before it is

at least 3-1/2 years old.